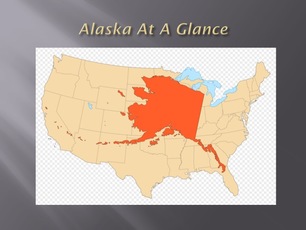

When asked about Alaska, I simply say, it’s my drug of choice. The geology alone is stunning, and running with the drug metaphor, is unavoidably addictive. You will not find higher mountains, larger glaciers, more abundant rivers, more spectacular glaciated valleys or greater wildlife diversity and abundance anywhere in North America. Considering that the U.S. purchased Alaska territory, a land mass one fifth the area of the entire lower 48 states, for $7.2 million dollars or 2 cents per acre, Americans have benefited immensely from that real estate deal. Surprisingly, more than 85% of this entire land mass is public lands managed by the state, the federal government and Alaska Native corporations.

The area colored orange in the southeast denotes the Tongas National Forest, largest national forest in the U.S.

The area colored orange in the southeast denotes the Tongas National Forest, largest national forest in the U.S.

My Alaska stories begin in 1970 with a float plane ride from Bethel Alaska, near the Bering Sea, to remote tributaries of the Kuskokwim River, compliments of the Alaska Department of Fish and Game. Here my crew and I will camp for many weeks and conduct salmon surveys, all part of a comprehensive management program designed to sustain Kuskokwim River salmon populations – it’s my first field biology job and I’m more green behind the gills then Ray Baxter, project director (my very first boss), ever imagined.

Chasing my photography and fly fishing passions, I returned to Alaska a few times over many years while enjoying a great teaching career, part of which included leading inbound and international natural history tours. In 2001, my ambition to return to the wilds of Alaska was inspired by a presentation of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge at a birding festival in California. One phone call to a dear friend in the US Fish and Wildlife Service blasted open opportunities for the next 12 years to extensively travel throughout Alaska conducting migratory bird surveys, mostly shorebirds, waterfowl and seabirds. Twelve years spending time in extraordinary national wildlife refuges, national parks, U.S forests, Native lands and biological preserves - Holy Cow!

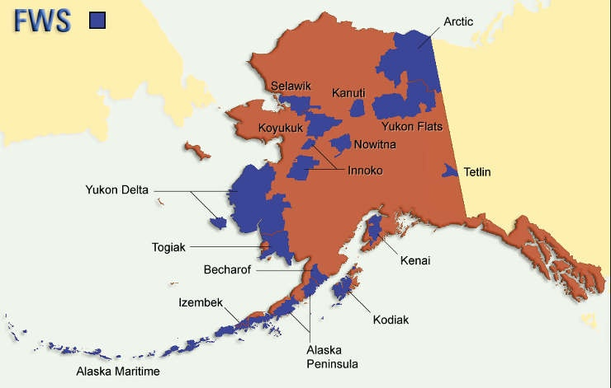

During my tenure in Alaska I learned that the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) manage all national wildlife refuges – a partnership exits in some cases with the U.S. Geological Survey. All of Southeast Alaska - the Inland Passage - and parts of Yakutat AK comprise Tongas National Forest, the largest national forest in the U.S. For a geography perspective of Alaska, refer to the maps.

Chasing my photography and fly fishing passions, I returned to Alaska a few times over many years while enjoying a great teaching career, part of which included leading inbound and international natural history tours. In 2001, my ambition to return to the wilds of Alaska was inspired by a presentation of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge at a birding festival in California. One phone call to a dear friend in the US Fish and Wildlife Service blasted open opportunities for the next 12 years to extensively travel throughout Alaska conducting migratory bird surveys, mostly shorebirds, waterfowl and seabirds. Twelve years spending time in extraordinary national wildlife refuges, national parks, U.S forests, Native lands and biological preserves - Holy Cow!

During my tenure in Alaska I learned that the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) manage all national wildlife refuges – a partnership exits in some cases with the U.S. Geological Survey. All of Southeast Alaska - the Inland Passage - and parts of Yakutat AK comprise Tongas National Forest, the largest national forest in the U.S. For a geography perspective of Alaska, refer to the maps.

Interior Alaska

Yukon Flats National Wildlife Refuge - NWR

Camp Lake in Yukon Flats NWR ©mike denega

Camp Lake in Yukon Flats NWR ©mike denega

Seasonal and permanent wetlands in California, where I live, are comparatively small, disconnected refuges surrounded by a sea of agriculture. With few exceptions, rivers are sophisticated plumbing systems designed and built by humans to meet agriculture and municipal water demands.

Flying over the Yukon River in a 185 Cessna bush plane, roughly 300 miles downstream of its origin in the Yukon Territory, I am awestruck by the breadth and beauty of the landscape, which I later learn is 8.6-million plus contiguous acres of the Yukon Flats NWR, the third largest National Wildlife Refuge – bigger than Maryland and Delaware combined. There is no interruption by human development during my aerial view of this wetland area – created by the Yukon River – with more than 40,000 lakes and ponds representing one of the greatest waterfowl breeding areas in North America.

My first migratory bird project in Alaska will begins when my bush plane lands at Camp Lake in Yukon Flats NWR in early July, 2001. I anticipate the environmental conditions to be very tough – difficult hiking, mosquitos, bears, etc. – but the rewards in studying the nesting success of Lesser Scaup, known as a diver ducks, will outweigh the hardships. Welcome to the Yukon Flats NWR.

Flying over the Yukon River in a 185 Cessna bush plane, roughly 300 miles downstream of its origin in the Yukon Territory, I am awestruck by the breadth and beauty of the landscape, which I later learn is 8.6-million plus contiguous acres of the Yukon Flats NWR, the third largest National Wildlife Refuge – bigger than Maryland and Delaware combined. There is no interruption by human development during my aerial view of this wetland area – created by the Yukon River – with more than 40,000 lakes and ponds representing one of the greatest waterfowl breeding areas in North America.

My first migratory bird project in Alaska will begins when my bush plane lands at Camp Lake in Yukon Flats NWR in early July, 2001. I anticipate the environmental conditions to be very tough – difficult hiking, mosquitos, bears, etc. – but the rewards in studying the nesting success of Lesser Scaup, known as a diver ducks, will outweigh the hardships. Welcome to the Yukon Flats NWR.